An article in the British Medical Journal by its former editor-in-chief and a supporter of Extinction Rebellion.

The text is an edited version of a speech given by Fiona Godlee for the annual “Sermon before the University” in the chapel of King’s College, Cambridge.

Have you ever sat down in the middle of the road? I did it the other day, in Regent Street in central London, as part of a protest organised by Extinction Rebellion. There were 10 000 of us sitting in the road, from Oxford Street to Piccadilly Circus.

The next day, while XR protesters were marching, chanting, and glueing themselves to buildings, I joined a group of doctors and nurses, sitting quietly in the middle of the road on Lambeth Bridge. Fifty or so health professionals in hospital scrubs spending their weekend in civil disobedience and risking arrest. Why?

I’ll answer that, but first I need to issue a health warning. There is some bleak information coming. Please don’t despair. There are also solutions that offer hope.

So, back to Lambeth Bridge. The doctors and nurses were there because, like me, they have understood that the climate crisis is a health crisis. Like me they are scared by what they know, and they feel compelled to act. As health professionals, it’s our job to protect and promote health. We are also concerned for our own families—children and grandchildren, nephews and nieces.

Sadly, the climate science is unequivocal. The world is heating up. The past seven years have been the seven warmest ever recorded. And climate scientists have long been in agreement that, if average global temperatures increase to 1.5°C above the pre-industrial average, there is a high likelihood the planet will tip into irreversible climate change, with catastrophic consequences for life on Earth.1 Current global average temperatures are around 1°C above the pre-industrial average. At current rates of warming, the scientists estimate that we will hit the 1.5°C tipping point in or around 2033.2 That’s in 11 years’ time.

No wonder we are scared. Unless this temperature rise is averted, the impacts on human health and life will be immense.

Climate change is already causing injury, disease, and death around the world, through heatwaves, wildfires, storms, floods, droughts, increased infectious disease and mental ill health. Climate change also threatens the very things that lead to good health, like clean air, safe drinking water, nutritious food, safe shelter, financial stability, social equality, access to healthcare and social support.3 The impacts fall heaviest on the world’s poorest, who have contributed least to greenhouse gas emissions.

Meanwhile rising temperatures are shrinking the area of liveable and productive land, displacing more people, adding to the numbers displaced by recent wars, wars that are themselves fuelled, as in Ukraine, by the world’s addiction to oil and gas. The climate crisis is becoming a humanitarian crisis. Conservative estimates put the number of climate refugees by 2050 at more than 1 billion.4

Burning fossil fuels also causes air pollution both inside houses and outside, causing nearly seven million premature deaths a year, from things like asthma, lung cancer, heart disease, stroke, premature birth, and dementia.5 This puts a huge and growing burden on healthcare systems. For the doctors sitting with me in the road, one thing is certain: they can’t protect their patients if we don’t protect the planet.

If the cause of the crisis is clear, so too is the remedy. Carbon dioxide stays in the atmosphere for centuries. Emissions must be radically reduced.

And it’s urgent. In the chilling words of Hoesung Lee, chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, speaking at the launch of the latest IPCC report:6 “Any further delay in concerted global action will miss a brief and rapidly closing window to secure a liveable future for all.”

As a world we have shown we can respond to immediate threats—covid, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—but apparently not to the slower, existential catastrophe of climate change. In the film “Don’t Look Up” the world has six months to avoid being destroyed by the incoming meteorite. But incompetent vain glorious politicians and commercial vested interests stimy those who could avert disaster.

Public inertia and fear of change also play their part. But the mood is shifting, especially among younger people. Time frames are tightening around commitments to achieve net zero. Pressure is building on institutions of all shapes and sizes to cut their own emissions, to divest from fossil fuels and reinvest in green alternatives.

Here Cambridge has things it can be proud of. It was the birthplace of the NHS Sustainable Development Unit, which sowed the seeds for the NHS to become the first health service in the world to show how it will reach net zero by 2040. And the university has committed to divest. It has set up Cambridge Zero, which is working to achieve net zero and is pulling together the university’s impressive research and educational resources to accelerate technological, economic, public health and social action.

This is all good. But there is much more to be done, by Cambridge, and all universities around the world. Are you putting climate in all policies? Are you moving swiftly to 100% renewable energy? Are you using your land and property portfolios to rewild and to install renewable energy sources for yourselves and local communities? Are you fully using your considerable convening powers to bring about change? Is the food you serve local, seasonal, and plant based? Will you stop reimbursing air travel? Should you now cut ties with the fossil fuel industry, including in Cambridge’s case, research, and collaboration with BP and the offshore drilling company Schlumberger, as the Students’ Union is asking you to do? 7

Each of us has a part to play. In the face of Russia’s threats, the EU has asked its citizens to help reduce dependency on Russian oil and gas, by turning down the heating or air conditioning, eating less meat, using public transport, and flying less.8 These are things all countries should be encouraging, regardless of this current terrible war. People around the world have shown that they respond well to being told what to do in a crisis. We need a covid style response to climate change. Instead of “Stay home, Protect the NHS, Save Lives” why not “Cut carbon, Protect the planet, Save humanity”?

Leeds University has come up with six things that cost nothing and that would, if done by everyone in wealthy countries, cut global carbon emissions by 25%: eating a largely plant based diet, buying no more than three new items of clothing a year, keeping electrical products for at least seven years, flying only occasionally or not at all, getting rid of your car or keeping your current car for longer, and making one green shift such as moving to green energy, insulating your home or changing pension supplier.9

We can all do these things, but we must also keep up the pressure on our governments, banks, businesses, and institutions. An editorial published last year in more than 200 medical journals around the world called on wealthy nations to do “much more, much faster.”10

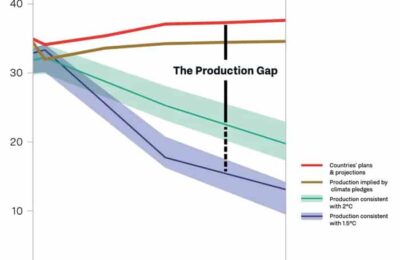

For Peter Kalmus, a lead author of the IPCC report, the failures of government and big business have become intolerable. Having tried all traditional means of influence available to him as a scientist, writer and campaigner, last month on 6 April, he chained himself to the railings of JP Morgan in Los Angeles, saying he felt “morally compelled to sound the alarm.” JP Morgan is the world’s largest investor in fossil fuels, pumping billions of dollars a year into the industry. According to the United Nations Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, such investment is “economic and moral madness.” Guterres went on to say: “Climate activists are sometimes depicted as dangerous radicals, but the truly dangerous radicals are the countries that are increasing the production of fossil fuels.”

These words are important. Newly passed legislation makes protest and civil disobedience more difficult and riskier. Responding to the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill on 27 April, the CEO of Amnesty International UK, Sacha Deshmukh said: “This is a dark day for civil liberties in the UK. This deeply authoritarian bill places profound and significant restrictions on the basic right to peacefully protest and will have a severely detrimental impact on the ability of ordinary people to make their concerns heard.”

Here’s where we get to the hopeful bit. For me the fact that Peter Kalmus did what he did and Antonio Guterres said what he said are reasons to be hopeful. Even though driven by desperation, their actions and words suggest that concern for the climate has finally leapt into the forefront of public discourse and cannot now be swept aside.

And crucially the world doesn’t need to be a harder, more difficult place just because we find different solutions for looking after the planet. There will be substantial positive benefits to health and society if we can reduce our reliance on fossil fuels: cleaner air, cleaner water; active travel and plant based diets will improve our physical and mental wellbeing, as will engagement in rewilding and community action. We could achieve greater global justice and social equality, restored biodiversity, fewer displaced people, perhaps fewer wars.

My own small act of rebellion ended without me being arrested. But others were arrested that day, including seven health professionals. Their quiet dignity while they were spoken to by the police, searched and driven away, was profoundly moving. And it left me with an enduring sense that the tide is turning, that minds can be changed, that small acts of defiance can make a difference. It felt, and feels, like hope.

But it also makes me wonder. How will we be judged by today’s young people, and by future generations? We who knew so much and did so little? Or we, who not only knew but understood and made climate action our one overriding priority; who acted, as nations, institutions, and individuals, with urgency, integrity, and courage, to build a better, fairer, healthier world. What did we do? What did you do? What will you do?

References

Footnotes

-

Competing interests: FG is a trustee of the Eden Project, chair of the Youth Environmental Service, an ambassador to the UK Health Alliance on Climate Change, and a Bye Fellow of King’s College, Cambridge.