From Unearthed

Pulchérie Amboula’s life has revolved around the land she farms on the Batéké plateaux, a vast, undulating savannah in the Republic of the Congo. She inherited it from her late father and grows cassava, from which she makes and sells foufou, a staple food in the region.

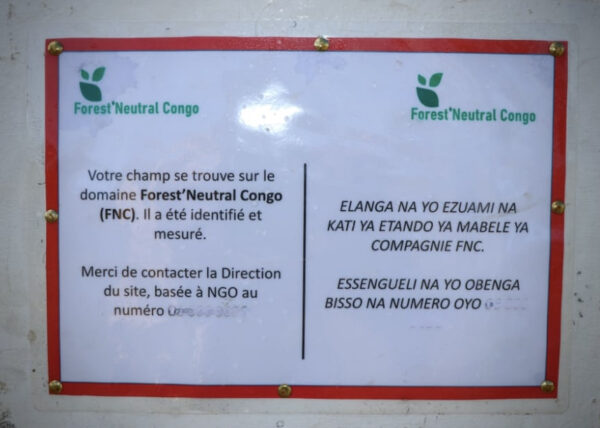

But since the launch of a tree-planting project at the end of last year, her life has changed. Now, she says, if she tries to access the fields, men in pickup trucks follow her tractor out until she leaves. Nearby, a laminated sign is tacked onto a small block of wood which reads, “your field is situated within the area, Forest Neutral Congo (FNC). It has been identified and measured.”

“Since this project arrived here, we no longer work. With grandchildren and children, how are we going to live?” she asks.

“The kids will no longer study. We no longer have fields, how will we pay for their schooling?…If you fall sick today, where will you get the money to get treatment? I feel like these people came to kill us on our own land.”

The people Amboula refers to are guarding the land on behalf of oil giant TotalEnergies, for a major new carbon offsetting project that it announced last year. Acacia trees will be planted across 40,000 hectares of land, which Total says will sequester more than 10 million tonnes of CO2 over 20 years. The first planting began around a year ago.

The project will generate carbon credits, a financial tool designed to fight climate change by commoditizing each ton of CO2 captured by newly planted, or protected, trees. Total will use the credits to offset some of its own emissions. This practice, known as carbon offsetting, is increasingly popular with fossil fuel companies and other corporations, as a way of meeting their net zero targets.

To gain access to the land, Total partnered with FNC to plant trees in the Lefini reserve, part of the Batéké Plateaux. FNC, which has leased the land from the Congolese government, is a subsidiary of Forêt Ressources Management (FRM), a French consultancy firm which claims to promote sustainable logging practices in Central Africa.

But the project has come at a cost for families on the Batéké plateaux who have lived off of this land for generations. An investigation by SourceMaterial and Unearthed has found that the land set aside for Total’s offsetting project was requisitioned for the purpose by the Congolese government in a law passed more than a year before consultations with local communities concluded. The government later signed a lease promising to evict local people with ancestral claims to the land.

Representatives of some families from these communities later received a nominal payment, worth around $1 per hectare. Land in the area has previously been rented out for 16 times that amount, according to two sources with knowledge of the local agricultural economy.

During two recent visits to the area, half a dozen farmers told SourceMaterial they had been prevented from planting or tending crops.

Some farmers who can no longer access their fields said they were not consulted and received no money.

It is not clear how the money paid to family representatives has been distributed among other people in the community whose families have long farmed the land. The total number of people who depended on this land for their livelihoods is also unknown – one unfinished survey by a Congolese civil society group called the Justice and Peace Commission counted 160, but the group believes the real figure is higher.

In a joint statement, Total and FRM said work was underway to “establish a complete picture” of the people who had been affected by the project, and to offer them “appropriate remediation” for “negative impacts”.

“In March 2022, [Total and FNC] launched an assessment to identify the project’s potential impacts and to mitigate negative impacts that could not be reduced,” said a spokesperson for the two companies. “This will establish a complete picture of those who are affected by the project in the overall project area (55,000 hectares) and will identify a remediation action plan, including livelihood restoration measures that comply with international standards. Results will be complete and made public in 2023.

“All [cassava] fields on the site have remained untouched and all the stakeholders historically present on the site are being identified and will be offered alternatives for future farming rotations, including prepared lands or other appropriate remediation to be defined with them.”

Every tree planting offset, or forest conservation offsetting project is likely to have a land conflict to a higher or lower degree

Total and FRM also told Unearthed that the land “was not requisitioned, as it had belonged and still belongs to the state.”

However, land rights in the Republic of the Congo are complex. The legacy of colonial law means that the state is the official owner of most land, but in practice families have long used the land on the Batéké plateaux. It is passed down from generation to generation, with the process managed through tradition and local land chiefs.

While the law recognises these customary land rights in principle, in practice land must be registered with the government; experts say this process is too expensive and convoluted for most people. Even then, the law still allows the state to take control of the land for its own purposes – in this case to lease it out to FNC.

The government of the Republic of the Congo was approached by Unearthed for this article, but said it was unable to respond in the time available.

The ‘eviction of all alleged landowners’

Documents obtained by SourceMaterial and seen by Unearthed show that:

- Government ministers met with “potential landowners” from June to July 2020, as part of an “inter ministerial mission” to raise public awareness of Total’s project. By the end of these meetings, a “participatory map” demarcating the land had been drawn up, with the names of landowning families written across each of their plots.

- Two months later, on 18 September 2020, the government passed a law making the land – a 70,089 hectare wide area called the Lefini reserve – the “private property of the state.” It reads: “The land reserve (…) is declassified from the public domain and incorporated into the private domain of the State, with a view to the conclusion of an emphyteutic lease between the government and the company FNC.”

- Six weeks after that, on November 3rd 2020, the government signed a contract leasing the land to FNC for sixty years. It stated that the government must, “guarantee the lessee the eviction of all alleged landowners, holders of traditional and customary rights who would lay claim to the land.” The yearly lease costs FNC $105,634, with an additional payment of $27,892 to a fund for local development.

- It was not until a year later, in September and October 2021, that the government held two rounds of “negotiations” with local communities. At the end of these meetings, the representatives of nine families signed a memorandum of understanding in which they agreed to accept a “symbolic” lump sum of 50m central african francs, or just over US$80,000. This franc symbolique payment was equivalent to around one dollar per hectare of land. The document states that the payment is made to the families “with the view to clearing their rights of use” to the land.

- The deal between the government, FNC and Total was finalised in law – in January 2022. The official record – signed by the president – states that Total will fully finance the project.

According to Total’s press officer, Gael Baudet, the oil company is “subleasing the area from FNC, and FNC from the State of Congo to whom it belongs.” He would not say how much Total is ultimately paying for the land, writing that the matter is subject to “contractual confidentiality”.

Carbon credits

Total has claimed the credits will be accredited under the Verified Carbon Standard scheme, which is administered by Verra, the biggest issuer of carbon credits in the world. However, Verra told Unearthed that it had not yet begun any substantive review of the project and there was no guarantee it would be approved.

Verra’s spokesperson said it could not comment on Total’s project as the organisation had not yet reviewed – or potentially even received – any information about it from Total. Verra’s accreditation process allows project activities to begin before the project is reviewed.

However, he claimed that carbon credit projects could not be accredited without extensive public consultation with affected communities, and that therefore projects imposed against the wishes of local communities would fail to get accreditation.

“Anyone who tried to steamroller smallholders… would fail to both get results and pass the extensive review and public consultation required to generate carbon credits,” he told Unearthed. “Credits can’t be issued until the project has gone through extensive expert review and public consultation backed by dozens or even hundreds of random interviews with local communities.”

Total did not respect the human rights of the population in the project they brought here

Jutta Kill, a biologist and carbon offsetting expert who consults for the World Rainforest Movement told Unearthed that the land rights issues with offsetting are a systemic and inevitable problem.

“Every tree planting offset, or forest conservation offsetting project is likely to have a land conflict to a higher or lower degree. Why is that? Because by definition, a project developer has to show that the threat of deforestation has been diverted or that the land use has been changed, so that more carbon is stored on the land. This inevitably means that the current land users will be pushed to change the way they use the land – and generally, in the carbon market, these users will be indigenous peoples or peasant farmers and the project developers will come from industrialised countries.”

Controversial consultations

The consultation process between the government and local people over the Lefini reserve has led to confusion, disagreements and complaints by and among affected communities.

An internal government document seen by SourceMaterial and Unearthed describes the consultation process and details two disputes with groups of local families or representatives who made a claim to the land. One group seems to have been eventually compensated; the other does not.

In its analysis of the consultation process, the document concludes that “the transfer of lands of the Lefini reserve was complex”, in part because of a “total absence of a procedure for the recognition of customary lands in the locality”.

There is also evidence that in at least one case a family was recognised as having land rights by the inter ministerial mission, but received no share of the final payment. The plot of the Nkonon family group was marked out on the government map as being part of the new reserve. But the family was not present at the ceremony and received nothing at all.

The internal government document states that their land “was withdrawn from the list” because there was no representative.

However the land chief for the Nkonon land, Maixent Jourdain Adzabi, told SourceMaterial that his family was “never included” in the consultation process and that they no longer have any work.

“Today, populations are crying, and bitterly. And us, our children? We raise them based on our fields. We work, we find money to get them into school. The project is for how many years? And our future children that will be born, will eat what? And their wives and their children, how will they live? Where will they work?”

Brice Mackosso, deputy coordinator of the Justice and Peace Commission, an NGO linked to the Catholic church, told SourceMaterial and Unearthed: “Total did not respect the human rights of the population in the project they brought here. They cannot hide behind the weakness of the Congolese law and behind the government’s failure to consult their own people. ”

Total and FRM told Unearthed that the development of the project would take customary rights of use into account.

“An assessment is underway to finalise the mapping of stakeholders and to propose and implement the measures that will allow them to be co-beneficiaries of the project,” said their spokesperson in a statement.

“In addition to mechanisms, such as access to farmland and machinery, the project will offer them a stake in the agroforestry value chain, allowing them to enjoy the benefits of the region’s new socio-economic development.”

The results of the companies’ “assessment” will be made public next year.

The companies made no comment on what local farmers should have done over the course of the last year when they were unable to access their land.

Total and FRM’s statement said that in the short- to medium-term the project will “produce significant social co-benefits” through “employment opportunities” – including “for women and indigenous populations” – such as the hiring team leaders, seasonal workers, engineers and technicians.

It added: “The project will also foster farming practices that are well known in the neighbouring part of the Bateke Plateaux by launching a 2,000 hectares acacia/manioc agroforestry system in partnership with local farmers. This will improve the manioc yield and produce alternative sustainable wood fuel for local use (replacing wood fuel from deforestation)…

“It also includes a local development fund dedicated to the local communities, financing social projects in nutrition, health, and education. The development fund is being designed and will be launched in the coming months in line with the project plan.”

Symbolic payment

When Rosalie Matondo, the Congolese forestry minister, visited Ngo by helicopter in October 2021, a group of people gathered to hear her speak. They sat in rows of plastic chairs underneath a tarpaulin to keep off the rain, while Matondo perched at the front. “We have come here, very respectfully… so that this project can have your blessing… be proud to tell yourselves today that you, you, are engaged in the fight against climate change,” she said into a microphone.

Soon after this, the symbolic payment was made to some of the landowning families, upon their signing of the memorandum of understanding. This money was distributed to other families who use the land, but it is not clear how this process took place.

Some of those who signed this document mistakenly understood it to be a contract; some say they have never seen or were not given a copy and have some regrets about accepting the money.

Ragan Ndzoro, who received some of the money, told SourceMaterial that he had given up his land out of a sense of duty to the government and hoped the project would benefit future generations.

However, he said that “no one owns a copy of the contract” and that the money paid “is insignificant because each [parcel of] land involves several people. To the point where in certain families, some benefited from 1,000 CFA, other 2,000 CFA – you know, we are Africans. African families are very big. And especially, when there is a money issue, even if there are people who have moved to France or elsewhere, if they hear about money problems, they all return to the cradle to reclaim this sum. What can we do, what can we say?”

A video showing men and women writing their names on a piece of paper while a government official stands beside them, pointing at where to sign, was posted on the Ministry of Forestry’s facebook page. The caption above it reads: “Rosalie Matondo went to Ngo in the Plateaux Department for the official handing over of the symbolic francs to the landowning families listed in the Lefini land reserve… This is part of the TOTAL ENERGY project, which will be launched on November 6, 2021.”

Neat rows of leafy acacia seedlings now stretch across parts of the Batéké Plateaux. Portacabins house workers responsible for watering them and looking after nurseries of young trees. Billboards emblazoned with Total and FNC’s logos line mud roads running past the plantations, advertising the “Batéké carbon sink” project, which will “increase the surface area of national forests” and “its capacity to store carbon”.

Meanwhile, farmers who used to work this land can no longer cultivate their fields and say they are struggling to feed their families. “Their trees over there are for their benefit, not ours,” said Amboula. “Let them give us back our space and leave, far from the villages, so that we can do our fields. We have no interest in their money.”

The similarity between this process in the Republic of Congo, and the earlier depopulation of Ireland and the Highlands of Scotland, is uncanny.

In both cases, wealthy individuals and companies replace local farmers with monocultures of deer,sheep and pine trees, or, in this case, Acacia trees.

Recent understanding of “rewilding” projects suggest that having human farmers on the land IMPROVES bio-diversity. An endless forest of one tree species will only appeal to a few species of creature that rely on that specific tree.

Wildlife benefits from a mosaic of farmer-cultivated land, open grassland, patches of mixed forest and scrub etc.

This is a Lose/Lose situation, just to allow fossil-fuel companies to carry on burning oil and gas.