Israel has an international reputation for its high-tech agriculture. Its companies offer everything from the latest in drip irrigation systems to pesticide-spraying drones. But Israeli agribusiness has developed out of a militarised and illegal occupation of Palestinian lands and, in recent years, its growth is closely tied to the promotion of Israel’s diplomatic and economic agenda abroad. Much of this agro-diplomacy is carried out by a handful of little known companies led by former defence and secret service officers with high-level political connections. The companies they own specialise in expensive agricultural projects that are structured through offshore financial vehicles, involving the purchase of Israeli products and technologies and, often, connections with arms deals. Africa is a key target, but Israeli agribusiness projects are mushrooming around the world– from Colombia to Azerbaijan to Papua New Guinea. Few of these projects produce tangible benefits for local communities. But the consequences, from land grabbing to debts, can be severe and long-lasting. This report pulls back the curtain on the overseas activities of Israeli agribusiness and considers the consequences for local people as well as the ongoing occupation of Palestinian lands.

It is mid-May 2022, and Israel’s Minister of Agriculture, Oded Forer, is holding a press conference in the rural Nagorno Karabakh region of Azerbaijan, just a few kilometres from the border with Iran. This, as an official Israeli press release notes, is the first time an Israeli minister has travelled to the Iran border.

[1]The stated purpose of Forer’s mission is to visit a multi-billion dollar agricultural development project that the Azerbaijan government is constructing in areas that it recently reclaimed from Armenia, thanks, in large part, to Israeli arms and military technologies, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

[2] The “Smart Villages”, as the project is called, are also being built with Israeli technologies, but in this case agricultural ones.

“Thanks to the close strategic relationship between Azerbaijan and Israel, [Azerbaijan’s] President Aliyev decided that Israel was to be Azerbaijan’s key partner in developing agriculture in Azerbaijan in general and in Nagorno Karabakh in particular”, reads the Israeli press release.

[3] Even the concept of “smart villages” or “agroparks”, as they are also called, is said to be inspired by Israel’s

moshav or “village farms” that were established in Israel in the 1950s and early 1960s, in the process of early colonisation of Palestinian lands.

[4]Several Israeli agribusiness companies are part of Forer’s delegation. They include the irrigation company Netafim, the pesticides company ADAMA, and the dairy equipment and services company Afimilk.

[5] Israel’s main involvement in Nagorno Karabakh will be the design and construction of a large dairy farm, built with Israeli equipment, but Forer is also there to talk about expanding grain production so that Azerbaijan might export wheat and other cereals to Israel.

[6]Iran is concerned that the agriculture projects are a front for Israeli intelligence and military activities on their border. But people in Azerbaijan are worried about reports that the “Smart Villages” project is being used to enrich the family and friends of their President, Ilham Aliyev, who the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) has singled out for figuring most prominently in its stories on crime and corruption.

[7] The projects are supposed to support the resettlement of the 600,000 Azerbaijanis who were displaced from the war with Armenia. According to investigations, however, large areas of land have so far only been handed out to agribusiness companies connected to high-level politicians and Aliyev’s family members.

[8] Israel’s agricultural support to Azerbaijan could be directly benefiting these elites.

Agriculture has long been central to Israel’s political ambitions in Azerbaijan. The set of bilateral deals that then Israeli President Benjamin Netanyahu signed with Ilham Aliyev in 2016 had a focus on agriculture.

[9] That same year, the Israeli company TerraVerde Agriculture was contracted to build large greenhouse and cattle farming operations for an Azerbaijan company called Aqua Garden LLC.

[10] Soon after, the Israeli company Green 2000 was contracted to build a dairy farm, this time by the UAE-based company Agri Biz Two FZE.

[11]Both TerraVerde and Green 2000 have a history of operating in countries that are important buyers of arms from Israel. They got their start in Angola in the early 2000s, after the civil war had ended. The two companies were hired by Israeli arms merchants who had supplied weapons to the winning side. With the war over, the Israelis shifted into other areas of business, orchestrating multi-million dollar agricultural projects in war-torn parts of Angola, which, like in Azerbaijan, were loosely based on Israel’s “village farms”.

Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev meeting on May 1st, 2022 with Israel Minister of agriculture and rural development Oded Forer. Photo: Official web-site of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan

The Israeli agricultural operations in Angola produced few benefits for the local people, but they were effective in cementing ties between Israel and Angola’s ultra-wealthy political elites, and they generated huge sums of money for Israel’s emerging cluster of companies and businessmen specialising in overseas agribusiness projects (see Annex I). The Angola projects effectively became a model for other Israeli companies, and the actors behind the operations in Angola, and others who have followed in their footsteps, are now central to Israel’s efforts to promote its agribusiness and advance its political agenda across Africa, Asia and Latin America.

For over a decade, GRAIN has been monitoring the activities of Israeli agribusiness companies overseas. We have grown increasingly concerned by the role these companies are playing in expanding industrial agriculture, particularly in Africa, and how their activities appear to be connected to other political agendas. Despite their growing international presence and the attention placed on Israel’s digital agriculture sector, most of these companies remain relatively unknown, even in the countries where they operate. In this report, we hope to deepen the understanding of who these companies are and what impacts they may be having in the places where they are active.

An Israeli agro-military complex

The linkages between Israeli agribusiness and its military industry run deep. The country’s agriculture is a product of decades of a violent, militarised occupation of Palestinian lands and its army’s oppression of the Palestinian people. Israeli agribusiness companies have been shaped by this context– and continue to profit from it (see box: Rooted in apartheid).

The Israeli military is also an important source of personnel and technologies for Israel’s agribusiness companies. It would be hard to find a single Israeli company among the hundreds of agri-tech start-ups that exist today that does not have some linkage with the Israeli military or secret service.

For example, the irrigation company Netafim’s platform NetBeatTM was developed through a collaboration with a subsidiary of the Israeli state-owned military corporation Rafael Advanced Defence Systems. The software was initially developed for Israel’s Iron Dome short range missile defence system, which was used in the military attacks on Gaza in 2014, according to Who Profits.

[12] Netafim also partners with ALTA Innovation and SeeTree, two Israeli companies founded by naval veterans and former military intelligence officers that are developing agricultural applications from Israeli military technologies, like drones and sensors (

more information on Netafim in Annex I).

[13]This connection between Israeli agribusiness and its military extends well beyond the country’s borders. In Angola, Azerbaijan and other countries strategic in geopolitical terms for Israel around the world, the sale of Israeli military equipment and security systems overlaps with the sale of its agricultural technologies.

India for example has become, under President Narendra Modi, both Israel’s main arms recipient from 2017 to 2021, and a top destination for several Israeli agribusiness companies and irrigation specialists.

[14]Vietnam’s recent emergence as a major buyer of Israeli arms and surveillance technologies has coincided with the creation of several bilateral agricultural projects with Israel.

[15] This includes Israel’s commitment to invest US$100 million into a mega-dairy farm which is being constructed with Afimilk’s products and services (

see Annex I).

Also in Asia, the Philippines recently became a major buyer of Israeli arms and surveillance technology during the administration of its former strongman president, Rodrigo Duterte. On an official visit to Israel in 2018, Duterte told journalists: “My orders to my military is that in terms of military equipment, particularly intelligence gathering, we only have one country to buy it from them. That is my order specifically, Israel”.

[16] Soon after, Duterte’s government signed an “Implementation Agreement” for a US$800 million loan from Israel to buy solar-powered irrigation and fertiliser pumps from an Israeli company, the LR Group.

[17] The project stalled, as the Department of Agriculture found it hard to justify such a massive budget outlay.

[18] But with some voices in the new administration of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. pushing for the project to move forward and with the government already having signed new bilateral investment agreements with Israel covering agriculture, it seems the deal is still alive.

[19]In Papua New Guinea, the LR Group was able to implement several large scale agricultural projects, paid for by the local government and backed by Israeli banks and its export credit agency (Ashra).

[20] There, too, the LR Group projects emerged after a 2013 visit to Israel by then Prime Minister Peter O’Neill to discuss the sale of military equipment.

[21] Subsequent investigations by PNG Blogs revealed that O’Neill’s deal with the LR Group also included the creation of a private intelligence agency and secret paramilitary spy force, and the purchase of Israeli power generators.

[22] This latter deal became a major scandal in PNG,leading to the eventual arrest of O’Neill on charges of corruption and misappropriation of funds.

[23] O’Neill was later acquitted of these charges in October 2021.

[24] LR Group was not charged in this matter.

Similar operations have taken place on the African continent. In South Sudan, a former general of the Israeli military was sanctioned by the US Treasury Department on allegations that he sold agricultural projects to the country in 2015 as a cover for the sale of arms. Further investigations found that the agriculture projects were financed through an arrangement backed by oil sales to the Swiss commodity trading company Trafigura.

[25] The agricultural projects were constructed by TerraVerde, one of the Israeli companies building farms in Azerbaijan.

[26] In 2020 the sanctions against the former general were lifted.

[27]Meanwhile, another of the Israeli agribusiness companies active in Azerbaijan, Green 2000, is building four large-scale poultry, fish and greenhouse operations in different parts of Côte d’Ivoire, through a US$120 million project financed by Israel’s Bluebird Finance & Projects and the Dutch export credit agency, Atradius, both active in financing other similar projects.

[28] Since taking power in 2010, Côte d’Ivoire’s President Alassane Ouattara has turned increasingly to Israel for arms and surveillance technologies, with the assistance of his close personal friend and advisor, the Franco-Israeli businessman, Hubert Haddad.

[29] One of the Israeli companies to benefit from this relationship is the Mitrelli Group, which is owned by former founders and executives of the LR Group.

[30] Under a partnership with Mitrelli, Haddad facilitated several multi-million dollar deals with the government of Côte d’Ivoire, including, most recently, a 2,000 ha rice irrigation project.

[31]

Rooted in apartheid

Among the companies travelling with the Israeli Minister of Agriculture to Azerbaijan in May 2022 were several that have been singled out by human rights organisations for directly profiting from Israel’s illegal occupation of Palestinian lands.

[32]

According to Who Profits, Netafim’s drip irrigation technology, for example, was critical to establishing Israeli agricultural settlements in the West Bank and the Syrian Golan areas that Israel illegally seized in 1967. This comes at the expense of access to water for Palestinians.

[33]The growth of Israeli agribusiness is inseparable from the country’s on-going apartheid system, which not only involves the mass expropriation of lands from Palestinian farmers and Bedouin herders but also the destruction of traditional Palestinian food, fishing and farming systems– leaving remaining Palestinian food producers dependent on imported Israeli agro-chemicals and seeds. Agribusiness companies operating in the illegal settlements also benefit from tax incentives, cheap labour provided by dispossessed Palestinian farmers, as well as less stringent pollution regulations.

[34]The Oslo peace accords opened the door to more foreign investment and trade for Israeli agribusiness. Soon after, the government signed numerous free trade agreements that helped to double its agriculture, forestry and fishing exports, even if Israel remains a net food importer.

[35] Foreign investment increased, too. Several Israeli agribusiness companies were bought up and integrated into large global corporations (see Table 1). Others got financing from Israeli and foreign banks and financial firms, and some restructured in tax havens like the Netherlands.

[36] Israeli agribusiness soon became an integral part of the global agribusiness landscape, with Israeli companies and their products now featuring heavily on the frontlines of industrial agriculture expansion, such as the soybean plantations in Brazil or the fruit and vegetable export zones of Mexico’s Guanajuato state.

[37],

[38]While Netafim may be one of Israel’s best known agribusiness companies, and a regular fixture in Israeli government delegations, it is owned by the Mexican group Orbia since 2018. Netafim conducts much of its sales through a subsidiary in the Netherlands, giving it preferential access to many overseas markets through EU trade agreements and investment treaties. Through this setup, it can access markets in Africa that have restrictions on trade with Israeli companies and get funding from Dutch public agencies.

[39]

Agro-mercenaires

Israel’s foreign engagement in agriculture often focuses on “turnkey projects”, following a model that Israeli companies first developed in Angola. A turnkey project is one where a company is contracted to design, fund, develop and equip a facility, such as a greenhouse farm or livestock barn, and then hands it over to the client when it is fully operational. Many of the Israeli companies specialising in these projects, such as the LR Group or the Mitrelli Group are owned by or connected to politicians or officers of the Israeli military and secret service, Mossad (

see Annex I).

[40]The typical turnkey project starts with the arrangement of meetings between Israeli company representatives and high-level politicians from a country rich in natural resources. The Israeli company will propose different ambitious, multimillion dollar agricultural projects that will be equipped and built with the latest Israeli technologies, and the company typically offers to handle everything, from getting loans to construct the farms to managing the project.

While the “agriculture” component is the public face of the project, the real pitch is the financing. The projects that the LR Group and other Israeli agribusiness companies propose often create an opportunity for governments that have difficulty getting credit from regular channels to use backdoor routes. Through such agricultural projects, these companies have been able to secure hundreds of millions of dollars in financing from European and Israeli banks and export credit agencies that are then routed, in some cases, through the Israeli company’s offshore subsidiaries.

[41]Israel’s export credit agency (Ashra) is regularly involved in these projects. In 2021, it backed deals for a value of US$2.8 billion, all sectors included.

[42] Its financial capacities far outstrip Israel’s development aid agencies.

[43] When an Israeli agribusiness corporation approaches a government in the global South with a large-scale project, it usually offers at the same time a financial package through a loan from Israeli banks at low interest rates, insured by Ashra.

[44] In case of non-payment, the Israeli government pays the company, and the government of the country where the project took place becomes the debtor.

LR Group/Mitrelli Group project Aldeia Nova in Angola. Photo: Projeto Jovens Lúcidos em prol a defesa dos direitos da comunidade

For its part, the government hosting the project must guarantee the loans, in some cases on the sale of resources, like petroleum or natural gas. And, as can be seen in the case of Angola, it may make lands available for the project, even if this causes the displacement of local communities. Once the project is approved, Israeli companies and consultants are contracted to supply the management, designers, equipment and inputs.

Many of the projects are said to be based on the

moshav or “village farms” model that was once used to integrate immigrants to Israel.

[45] In the global South, these projects are usually top-down, with local communities excluded from decision making, and dependent on the import of Israeli technologies, like greenhouses, irrigation and hybrid seeds. As can be seen in Angola, the participating villagers are more like cheap labour for the company. They have to pay the company for the use of the houses, the infrastructure, the small plots of land and the inputs that they are supplied. Everything they produce goes to the company, and in return the villagers get very little, as they must pay off their debts (

see the case of Aldeia Nova in Annex I).

In several cases, such as in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Israeli projects collapsed once the loan money was used up and the Israeli consultants left. Many of the projects we have looked at appear to not be economical or adapted to local conditions, and cannot be sustained without new inflows of money. Meanwhile, governments still have to deal with debts from the projects that they guaranteed, even if it is difficult to determine how the funds were spent, and even if there are signs of possible corruption (see the case of Aldeia Nova in Annex I).

The DRC Minister for Agriculture and a Vital Capital representative signing in 2019 a memorandum of understanding to launch five agro-industrial zones across the country, with a cost of US$150 million. Photo: DRC official twitter

The LR Group’s project in Suriname provides a good example of how these projects work. In 2014, the LR Group began discussions with officials from the government of Suriname for the construction of a large-scale dairy farm and “agricultural villages” in the area of Phedra.

[46] The LR Group was also pursuing a student housing project in Suriname at the time and, was reported to be in discussions with Suriname’s National Security Team about the provision of intelligence and security technologies.

[47]The two sides reached a first agreement in 2016 to provide an LR Group subsidiary with 2,000 ha for a cacao plantation in Phedra, which is yet to materialise.

[48] Then, in 2018, they concluded a second agreement for the Suriname Agro Industrial Park, a massive project that would include the construction of a 500 cow dairy farm and processing plant, a large poultry farm and a 600 ha crop farm in the districts of Wanica and Saramacca.

[49] According to documents leaked to the public in August 2019, LR Group would be paid to execute the plan, but all of the costs would be borne by the Government of Suriname, through a €67 million credit line from Credit Suisse, arranged by the LR Group.

[50]“It is a project of the LR Group that is executed with money from Suriname… It is not an investment, but a loan,” explained Winston Ramautarsing, chairman of the Association of Economists of Suriname. “The loan is in the name of Suriname, but the money goes directly to LR Group. Suriname would not be able to borrow such an amount on its own.”

Under the plan, Suriname is supposed to pay off the loan through the sales of eggs, milk and other foods produced on the farm. But Ramautarsing says the plan overestimates the market price for these products, and there are insufficient markets to absorb the quantity of production that is envisaged.

Ganeshkoemar Kandhai, chair of the country’s largest farmer organisation, also doubts the plan is viable. “They (LR Group) want to produce on a large scale, but the market is not big enough for that. At first, there was talk of exporting to the Caricom countries, but we don’t hear about that any more,” he says.

[51]“The tax money of farmers is being used to finance their competition — the same farmers who have been feeding the people for years under difficult circumstances, in all weathers”, he adds.

The other problem is that a large chunk of the initial loan from Credit Suisse appears to have disappeared. When questioned in Parliament, the Government of Suriname was unable to account for how close to two-thirds of the initial €67 million loan from Credit Suisse was allocated. LR Group did not respond to our questions regarding the financing of the project.

“This plan is not designed to develop the agricultural sector. It is a deal made in back rooms, the existing farmers were not even involved,” says Ramautarsing.

[52]

Suriname’s current government, which came to power in 2020, promised to exit the project, but the LR Group is reportedly refusing to even change the terms. Part of the problem is that the deal was structured through a guarantee from Sweden’s export trading agency which stipulates that 30% of the content of the project must be Swedish. In this case, LR group partnered with Swedish suppliers to provide the technology to the farm including the importation of pregnant cows from Sweden to Suriname.[53]

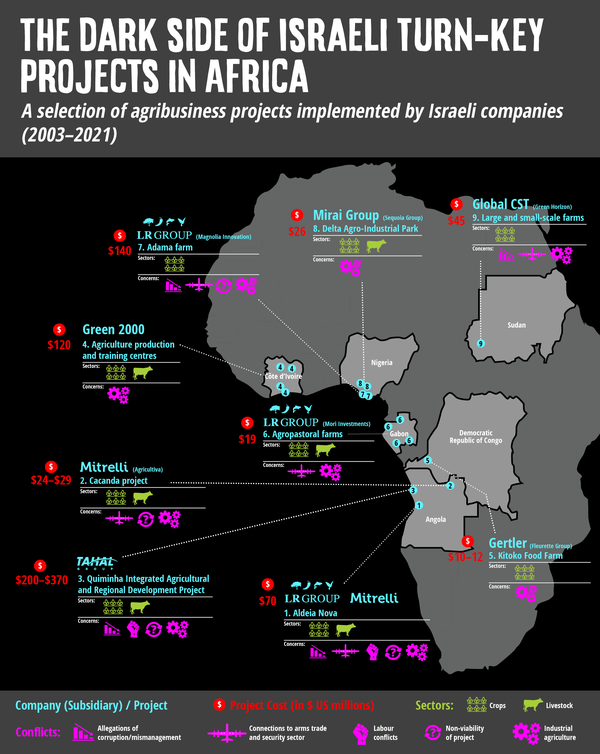

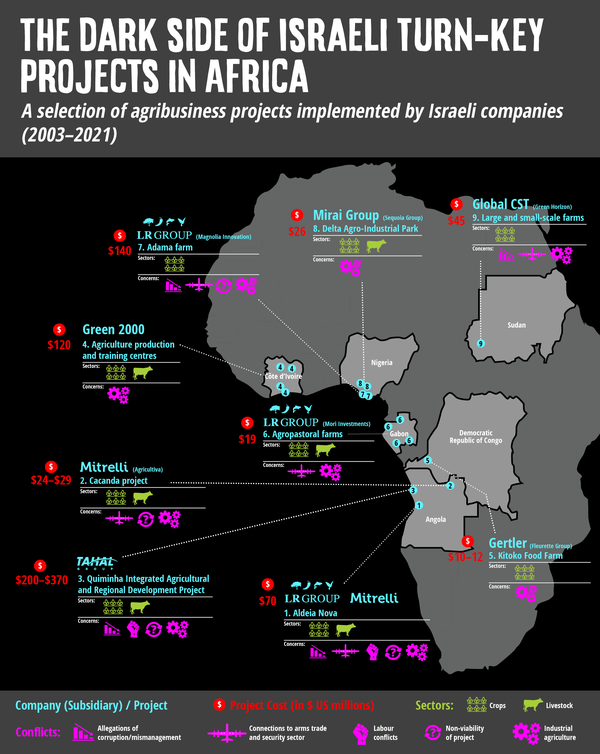

Surinam is not unique, LR group and other Israeli companies have developed costly turnkey projects implemented by Israeli contractors across many parts of the world and the benefits for local people are hard to find (see the infographic above).

Israeli agribusiness in Colombia

One of the key arms markets for Israel in Latin America is Colombia.

[54] Not surprisingly, Colombia is a major destination for its agribusiness as well. In 2013, the Israeli group Merhav signed a deal for a US$300 million ethanol project, which would involve the construction of a 10,000 hectare sugarcane plantation in the province of Magdalena. Both Banco do Brazil and Bank Hapoalim of Israel were to provide financing for the project. However, Merhav’s subsidiary Agrifuels Colombia was accused of having purchased 1,023 hectares illegally, and the project collapsed by 2016.

[55] Subsequent investigations connected the project to the “Lava Jato” corruption scandal in Brazil, through the participation of the Brazilian construction company OAS.

[56]Since 2014, LR Group is pursuing the development of cacao plantations and a dairy farm with the help of Colombian businessman Luis Vicente Cavalli Papa, a former representative of the Israeli state-owned company Isrex, which provided arms and irrigation services to Colombia in the 1990s.

[57]Just after the free trade agreement between both countries entered into force in 2020, an initiative to “boost investment and productivity in Antioquia’s booming agricultural-exports sector” was launched. It included LR Group and its subsidiary Bean & Co, among others. Managro, another Israeli company installed in Colombia since 2014, owns 1,000 hectares but plans to buy 3,700 more for Hass avocado production, and acquired recently Colombia’s Pacific Fruits.

[58]

A toxic harvest

Moayyad Bsharat works with the Palestinian farmer organisation, the Union of Agricultural Work Committees (UAWC). For years, UAWC has struggled to help Palestinian farmers remain on their lands, particularly in areas of the Occupied West Bank where Israeli settlements are illegally expanding. In October 2021, the Israeli government designated UAWC and five other internationally-respected Palestinian civil society organisations as terrorist groups, an accusation that was condemned by human rights organisations around the world.

[59]

Raid of UAWC’s offices by Israeli forces, 18th of August. Photo: UAWC twitter

Through his work with UAWC, Bsharat has documented how the Israeli occupation and apartheid system pushes Palestinian farmers into using seeds and agrochemicals sold by Israeli companies, thereby destroying their soils and biodiversity and leaving them in debt and poverty.[60]

“I used Israeli chemical pesticides in the previous two years. The biodiversity in my field was destroyed, especially bee hives and insects that are good for our crops. I rapidly got indebted with the sellers. So I decided to adopt agroecology,” says Gh. N, one of the young Palestinian small farmers that Bsharat works with.

[61]Jointly with big transnational agribusiness corporations, Israeli agribusiness companies are certainly part of the global agro-industrial model largely accountable for the climate and food crisis. The particularity here, though, is that the support received from the Israeli state and private operators enable those companies to operate in countries where big transnational agribusiness companies are hardly present.

Rooted in apartheid, big Israeli agribusiness companies, as well as Israel’s new generation of digital agriculture start-ups, not only push this model in Palestine, but increasingly to other parts of the world.

Few people have likely heard of LR Group, Mitrelli, Afimilk or Green 2000. Yet they are key actors in Israel’s foreign agribusiness dealings. They are deeply embedded in Tel Aviv’s strategy of opening markets for Israeli agribusiness companies and forging connections with political elites in countries that are strategic to Israel’s security agenda. These companies are seen to play an important role in shielding Israel from international pressure over its criminal dispossession of the Palestinian people and in spreading the expansion of industrial agriculture globally.

It is therefore critical to monitor and expose the activities of Israeli agribusiness abroad, not only to protect the interests of the people of those countries where they operate but also to build solidarity with the struggle of Palestinians against Israeli apartheid, settler-colonialism and occupation. In both cases, Israeli agribusiness is a threat to the fight for food sovereignty that peasant organisations are leading in Palestine and around the world.

Table 1. Largest Israeli corporations with agribusiness operations in the Occupied Territories and the global South

|

Companies*

|

Examples of operations in the Global South

|

Operations in the Palestinian and Syrian Occupied Territories

|

|

Afimilk

Owned by Kibbutz Afikim – Agricultural Cooperative Society Ltd. (Israel, 45%) and Fortissimo Capital Management Ltd. (Israel, 55%).

|

Large-scale dairy farms in Vietnam, Cambodia, PNG, China.

|

Reported to build and supply factories in settlements in the West Bank. [63] |

|

CBC Group (Coca-Cola Israel)

Dairy

Owned by Wertheim family (Israel) [64] |

Took over South African dairy giant Clover in 2019. Severe labour conflicts reported.

|

Controls a regional distribution centre in the Atarot industrial settlement in East Jerusalem. [65] One of its subsidiaries, Tabot Winery is installed in the Syrian Golan. |

|

ADAMA

Agrochemicals

Owned by Syngenta Group (China, 78.5%) [66] |

Sells herbicides, fungicides and insecticides in Latin America, Asia Pacific and the Middle East and Africa . [67] |

Herbicides and pesticides manufactured by the company have been used in agricultural experiments in the West Bank and the Syrian Golan. Partnership with a subsidiary of Urban Aeronautics military technology for aerial spraying. [68] |

|

Haifa Chemicals

Fertilisers and agrochemicals

Owned by: Trans Resource Inc. and TG Capital Corp. (USA)

|

Sells fertilisers in Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador, Brazil, South Africa, China, Thailand. [69] |

Provides fertilisers and services to settlements in the West Bank and the Syrian Golan. [70] |

|

ICL

Fertilisers

Owned by Israel Corporation (Israel, 45.6%) [71] |

Has fertiliser and specialty minerals plants in China, with subsidiaries in Argentina, Brazil, India, Kenya, Malaysia, Mexico, South Korea, Thailand, Uruguay.

|

Reported to supply several agricultural settlements in the West Bank, and to participate in agricultural experiments in the settlements in the Syrian Golan and the Jordan Valley. [72] |

|

Netafim

Irrigation

Owned by Orbia Advance Corporation (Mexico, 80%), Kibbutz Hatzerim (Israel, 20%).

|

Provides drip irrigation systems for monoculture and large-scale greenhouses in Latin America, Africa and Asia.

|

Supplies the settlements in the West Bank and the Syrian Golan with micro-irrigation products and services and has also participated in agricultural experiments in those Occupied Territories.

Partnership to adapt Israeli military technology used in attacks on Gaza and the Syrian Golan to civilian agricultural use. [73] |

|

Irrigation

Owned by Ministry of Finance of Singapore, via Temasek Holdings (China, 85%).

|

Supplies with irrigation equipment agricultural settlements in the West Bank and the Syrian Golan. [75] |

|

Hazera

Seeds

Owned by Groupe Limagrain Holding SA (France)

|

Sells hybrid seeds in Latin America, Africa and Asia through subsidiaries in China, Mexico, South Africa.

|

Israeli control over borders is part of a process to push Palestinian farmers to use commercial seeds sold by the company, associated to an agrochemical package. This model is not only unsustainable but contributes to the contamination of soil and water and to biodiversity loss. [76] |

|

Tahal

Water infrastructures [77]Owned by Kardan N.V. (The Netherlands – Israel)

|

Large-scale irrigation projects in Angola, Botswana, Ethiopia, Kazakhstan, Zambia.

|

Contracted on several occasions in recent years to build water infrastructure in the Palestinian Occupied Territories. [78] |

Data sources: Capital IQ, Preqin, Panjiva and the corporations’ websites [Last visit: 1 July 2022].

Note: GRAIN sent questions to Kardan N.V., LR Group and Mitrelli Group with questions about the activities they are involved with that are mentioned in this report. However, none of the companies provided answers to our questions.

________________________

[1]“The most senior Israeli official so far to reach so close to the Iranian border”, Office of the Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development, Communication, Media and Public Relations Division, Government of Israel, 19 May 2022,

https://www.gov.il/en/departments/news/visit_ministerneariran [Last visit: 29 August 2022].

[3]“The most senior Israeli official so far to reach so close to the Iranian border”, Office of the Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development, Communication, Media and Public Relations Division, Government of Israel, 19 May 2022,

https://www.gov.il/en/departments/news/visit_ministerneariran [Last visit: 29 August 2022].

[5]“The Minister of Agriculture, Oded Forer, departed this morning for a visit to Azerbaijan to promote the bilateral relations and maximize the trading potential for Israeli agro-tech companies internationally”, Office of the Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development, Communication, Media and Public Relations Division, Government of Israel, 16 May 2022,

https://www.gov.il/en/departments/news/azerbaijan_visit [Last visit: 29 August 2022].

[15]Israel was also a key supplier in 2016, as Vietnam was becoming the 8th largest arms importer and was modernising its army (

https://thediplomat.com/2016/10/vietnams-military-modernization/). In 2021, according to attorney Eitay Mack’s investigation, Israeli Cellebrite digital forensic technologies, whose sales have been directly monitored by the Defence Ministry Director General Amir Eshel, were used by the Vietnamese government to persecute bloggers, journalists and religious and ethnic minorities (

https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/tech-news/.premium-what-vietnam-is-doing-with-israel-s-phone-hacking-tech-1.10003831). Vietnamese tycoon Nguyen Thi Thanh Nhan, general director of AIC Group, reported to be a key broker in Israel-Vietnam arm deals has been linked to fraud and breach of trust (Yossi Melman, “Israel-Vietnam Arms Deals at Risk After Arrest Warrant Against Key Middlewoman”, Haaretz, 1 May 2022,

https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium.HIGHLIGHT-israel-vietnam-arms-deals-at-risk-after-arrest-warrant-against-key-middlewoman-1.10772845) [Last visit: 29 August 2022].

[19]See: Zachy Hennessey, “Israel and Philippines sign business agreement”, Jerusalem Post, 7 June 2022,

https://www.jpost.com/business-and-innovation/all-news/article-708763 ; “Philippines, Israel enter into a Joint Economic Cooperation to strengthen trade and economic ties”, Philippines Department of Trade and Industry, 9 June 2022,

https://www.dti.gov.ph/news/ph-israel-enter-into-joint-economic-cooperation/ ; Catherine Talavera, “Philippines eyes $150 million Israel investments”, Philippines Star, June 2022,

https://www.philstar.com/business/2022/06/10/2187304/philippines-eyes-150-million-israel-investments. The main proponent of the deal was former Secretary of Agriculture Emmanuel Piñol (see:

https://mannypinol.com/advocacy/new-neda-secgen-israel-offer-of-p40-b-loan-for-solar-irrigation-in-limbo/) and he was recently named food security adviser to the incoming National Security Adviser (see:

https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/topstories/nation/835796/pinol-to-serve-as-food-security-adviser-to-incoming-nsa-clarita-carlos/story/) [Last visit: 29 August 2022].

[25]The Israeli general was Israel Ziv and the company he owned was Global CST (see: David Mono Danga, “Green Horizon to increase production after US Lift ban on CEO”, The Insider, 29 March 2020,

https://www.theinsider-ss.com/green-horizon-to-increase-production-after-us-lift-ban-on-ceo/). In 2014, Global CST was reported to belong to the Mikal Group, an Israel private defence company (see:

https://www.eltiempo.com/archivo/documento/CMS-14952565). For more information on this project, see: OCCRP, “Sprouting weapons of war”, 17 July 2019,

https://www.occrp.org/en/investigations/sprouting-weapons-of-war [Last visit: 29 August 2022].

[28]See: John Basquill, “Côte d’Ivoire agriculture project secures Atradius-backed financing”, GTR, 2 September 2020,

https://www.gtreview.com/news/africa/cote-divoire-agriculture-scheme-secures-atradius-backed-financing; Atradius, “Annual review 2020”, 2020,

https://atradiusdutchstatebusiness.nl/en/documents/atradius_jaaroverzicht_2020_en.pdf ; and Guido Minnaert, “Green 2000, exporting rural projects to Ivory Coast”, Atradius News (n.d.),

https://atradiusdutchstatebusiness.nl/en/news/green-2000,-exporting-rural-projects-to-ivory-coast.html. Van der Hoeven reports a joint project with Green 2000 in Ukraine back in 2012. Bluebird Finance, Israel Discount Bank, and Green 2000 have been involved in a similar turnkey project in 2019 in Zambia, with a cost of US$47 million, backed by the Israeli and Dutch export credit agencies. The project was expected to be finalised by 2021 (Sanne Wass, “Financing closes for large Zambian agriculture project”, GTR, 8 January 2019,

https://www.gtreview.com/news/africa/financing-closes-for-large-zambian-agriculture-project/) [Last visit: 29 August 2022].

[33]Who Profits, “Netafim: from facilitator of occupation to global leader in sustainable agriculture”, March 2020,

https://www.whoprofits.org/updates/netafim-from-facilitator-of-occupation-to-global-leader-in-sustainable-agriculture/. While settlements face no restrictions and water shortages and capitalise on well-irrigated farmlands, the permits for Palestinians to build new water wells are constantly denied and their rainwater harvesting cisterns are often destroyed by the Israeli army (see: MA’AN Development Center, “Farming the forbidden lands. Israeli Land and resource annexation in Area C”, 2014,

https://www.maan-ctr.org//files/server/Publications/FactSheets/FFL.pdf; Amnesty International, “The occupation of water”, 29 November 2017,

https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/campaigns/2017/11/the-occupation-of-water/; and Al-Haq, on World Water Day, says Israel’s ‘water-apartheid’ denies Palestinians’ rights to adequate water”, Wafa News Agency, 23 March 2022,

https://english.wafa.ps/Pages/Details/128528) [Last visit: 29 August 2022].

[35]Important free trade agreements were signed with the European Union (1995), Canada (1997), Turkey (1997), and Mexico (1999). The sales of agro and water technologies increased by 1.5 times in the last decade, valued at US$6 billion in 2018. The main sectors are: fertilisers, chemicals, irrigation, equipment and materials for agriculture, seeds, and dairy and poultry farming. The European Union is the leading market, followed by Asia and South America (see: Israel Export Institute, “Agro and water technology. 2018 Annual report”, 2019,

https://www.export.gov.il/api//Media/ExportInstitueEnglish/Services/Economic%20Unit/Agro_and_Water_Technology_2018_review.pdf; “Israeli economy: past, present, future”, May 2021,

https://www.export.gov.il/en/economicsisraeleconomy; and Central Bureau of Statistics, “National accounts 1995 – 2020”, 2022,

https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/publications/doclib/2022/1859/t10.pdf) [Last visit: 29 August 2022].

[36]At least ten of the eleven Israeli commercial banks are ranged in the UN list of business operating in the Occupied Territories or reported by in the Who Profits database for supporting the settlement enterprise (see:

https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3872338?ln=es; and

https://www.whoprofits.org/flash-report/financing-the-israeli-occupation-the-current-involvement-of-israeli-banks-in-israeli-settlement-activity/) [Last visit: 29 August 2022]. Those banks also actively support Israeli agribusiness expansion in the Global South, giving loans or operating as intermediaries to guarantee the support of foreign banks and export credit agencies. Israeli private funds linked to insurance and finance groups fuel also those corporations. For example, Migdal Mutual Funds owns 5% of ICL shares, FIMI has ben the owner of Rivulis before selling it to Temasek, and has invested in Tahal. Tene Investment Funds has invested in Netafim and owns currently Gadot Agro Ltd. (previously Merhav Agro). Venture capital firms as Mindset Ventures or Finistere Ventures are also among those investing in agro-tech startups (Sources: Capital IQ and Preqin databases) [Last visit: 1 June 2022]).

[37]Brazil has become the main destination for ADAMA exports in the last two years. The Israeli corporation agrochemicals in the soybean champion states of Paraná (Londrina) and Rio Grande do Sul (Taquari). It sells drones and apps to detect weed infestation, for which it provides a large range of agrochemicals as glyphosate (see:

https://www.adama.com/brasil/pt/servicos-agtech). More information on the impacts of soybean monoculture in those regions can be consulted here:

https://www.biodiversidadla.org/Atlas [Last visit: 29 August 2022].

[39]See: “Water in agriculture in three Maghreb countries. Status of water resources and opportunities in Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia”, 2021,

https://prod5.assets-cdn.io/event/6099/assets/8383926062-5847dd91d1.pdf [Last visit: 29 August 2022]. In 2020, Netafim’s Dutch subsidiary Revaho benefited of the Dutch export credit agency Atradius support to the project in Côte d’Ivoire built by Green 2000 mentioned above.

[40]According to the French Institute for International Relations (Ifri), the Mossad’s role in Africa has been essential to help Israeli businessmen operations in the continent, besides engaging directly in the security of African leaders and training local security services. “It [Mossad] also builds bridges between former agents who work in the private sector and the Israeli state, that greatly facilitates the transfer of information” (Benjamin Augé, “Israel-Africa relations. What can we learn from the Netanyahu decade?”, Études de l’Ifri, November 2020, p. 14,

https://www.ifri.org/en/publications/etudes-de-lifri/israel-africa-relations-what-can-we-learn-netanyahu-decade) [Last visit: 29 August 2022].

[43]In Global South countries, international cooperation through such bodies as the Agency for International Development Cooperation (Mashav) and the Center for Foreign Trade and International Cooperation (CFTIC) of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development actively promotes Israeli agribusiness (see:

https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/generalpage/cftic_brochure/en/CFTIC_CFTIC%20short.pdf). Several Israeli NGOs are also becoming influential in the promotion of Israeli agritech in the Global South, such as Innovation Africa, IsraAID, or the Israeli branch of the Society for International Development (SID) [Last visit: 13 October 2022].

[45]In reality, the projects established overseas are not modelled on this myth of collective farming but emulate the Israeli reality of an agriculture based on capital intensive agribusiness, that promotes a colonial project where settlers displace Palestinian farmers from their land.

[46]The plan was first put forward in 2014 by the Israeli businessman Joseph Haim Harrosh, who was working with Tahal up until that time. He soon brought the LR Group into the project, for whom he then began to act as the representative in Suriname.

[56]See: “Vea por qué aparece el nombre de Colombia en el escándalo de corrupción de Petrobras”, 12 January 2015,

https://ajidemani.wordpress.com/2015/01/ ; and Pedro Cifuentes, “El ‘caso Petrobras’ salpica a obras hechas en Latinoamérica”, El País, 12 December 2014,

https://elpais.com/internacional/2014/12/12/actualidad/1418340985_541579.html. In 2017, Merhav’s CEO, Jose Maiman admitted its participation in the bribery payments received by former Peruvian president Alejandro Toledo from Odebrecht and Camargo Correa (see: “Las claves del caso Ecoteva, tras aprobarse segundo pedido de extradición para Alejandro Toledo”, Gestión Perú, 22 April 2021,

https://gestion.pe/peru/politica/alejandro-toledo-conoce-las-claves-del-caso-ecoteva-tras-aprobarse-segundo-pedido-de-extradicion-eliane-karp-caso-odebrecht-nndc-noticia/). According to the Panama Papers, Merhav’s CEO and vice-president, Jose Maiman and Sabi Saylan were also linked to five offshore companies, and both were intermediaries in the alleged bribes given to Toledo by Odebrecht and Camargo Correa (See:

https://offshoreleaks.icij.org/nodes/10009636; Jonathan Castro y Ernesto Cabral, “Operadores de Toledo manejaban red offshore con Mossack Fonseca”, OjoPúblico, 6 February 2017,

https://panamapapers.ojo-publico.com/articulo/operadores-de-Toledo-tenian-red-de-offshore-operadas-por-Mossack-Fonseca/ [Last visit: 29 August 2022].

[60]Moayyad Bsharat, “The reality of using commercial seeds from the viewpoint of small-scale farmers in the Jordan Valley (Jericho and Tubas governorates)”, Master Degree Thesis, Institute of Sustainable Development, Al-Quds University, 2020.

[61]Moayyad Bsharat, “The reality of using commercial seeds from the viewpoint of small-scale farmers in the Jordan Valley (Jericho and Tubas governorates)”, Master Degree Thesis, Institute of Sustainable Development, Al-Quds University, 2020.

[62]Other large Israeli corporations that operate in the dairy sector in Israel not mentioned in the table are: Tnuva, owned by the Chinese Bright Food Group Co. (ultimately controlled by Shanghai Municipal State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission) and Strauss Group, owned by Michael Strauss Assets Ltd. (Israel, 57.1%).

[66]The Syngenta Group is controlled by Sinochem Holdings (subordinated to the State Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of China).

[69]The Thai office is also in charge of the distribution in Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, Myanmar, India, Sri-Lanka; the South African one covers at the same time Zimbabwe, Zambia, Mozambique; and the Brazilian one distributes in Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia (see:

https://www.haifa-group.com/haifa-worldwide)[Last visit: 29 August 2022].

[71]Other ICL investors are: Migdal Mutual Funds (6%), Harel Insurance Investments & Financial Services (5%), Vanguard Group (1.6%), Meitav DASH Investments (1.4%), Halman – Aldubi Provinent and Pension Funds (0.6%).

[76]Moayyad Bsharat, “The reality of using commercial seeds from the viewpoint of small-scale farmers in the Jordan Valley (Jericho and Tubas governorates)”, Master’s Degree Thesis, Institute of Sustainable Development, Al-Quds University, 2020.